CPR for Pregnant Women- Step-by-Step Guide to Safe Maternal Resuscitation

Maternal cardiac arrest is a rare but life-threatening emergency that requires immediate and specialized care. The incidence is approximately 1 in every 12,000 deliveries, according to the American Heart Association (AHA). While uncommon, this statistic highlights the critical need for healthcare providers and bystanders to be prepared. The most common causes include hemorrhage, cardiovascular disease, amniotic fluid embolism, sepsis, and anesthesia complications, as identified by Jeejeebhoy et al. (2015). Recognizing these risks early can help in both prevention and prompt intervention.

Standard techniques must be adapted when performing CPR on a pregnant woman to account for physiological changes during pregnancy. These CPR modifications are essential to protecting both the mother and the fetus. Our article provides a clear, step-by-step approach to managing maternal cardiac arrest. This will help you respond effectively in this critical situation. Every second counts—being informed can save two lives.

Why Pregnancy Requires Modified CPR?

Pregnancy introduces significant physiological changes that make standard CPR less effective. To improve outcomes, specific CPR modifications are necessary when responding to a maternal cardiac arrest.

Aortocaval compression and reduced cardiac output

The enlarged uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava when the woman lies flat on her back, in the advanced months of pregnancy. This is known as aortocaval compression, and it can reduce cardiac output by 30–40% during the third trimester, as per the American Heart Association (AHA). This drastic reduction impairs blood flow to both the mother and the fetus, making chest compressions less effective. To counter this, left uterine displacement (LUD)—manually or by tilting the patient 15 to 30 degrees to the left—is essential during CPR for a pregnant woman.

Time-sensitive delivery decisions

For pregnancies beyond 23–24 weeks of gestation, the AHA emphasizes that resuscitative hysterotomy (emergency C-section) within 5 minutes of arrest offers the best chance for neonatal survival. This timeline underscores the urgency of initiating advanced interventions without delay.

Understanding these physiological changes is critical for improving survival outcomes. Modifying standard CPR in pregnant women is not optional—it is vital for saving both maternal and fetal lives.

Precautions and Initial Assessment

When responding to a maternal cardiac arrest, early recognition and appropriate action are crucial. The unique pregnancy physiology—including increased blood volume, altered respiratory function, and risk of aortocaval compression—requires immediate assessment and specific precautions to optimize survival for both mother and fetus.

Check responsiveness and call for help.

Start by checking the woman’s responsiveness and breathing. If she is unresponsive and not breathing normally, call emergency services immediately. Be sure to state clearly that the patient is pregnant. This prompts dispatchers to notify the appropriate team and prepare for interventions like perimortem cesarean delivery.

Assess gestational age

Quickly assess whether the pregnancy is visibly ≥20 weeks of gestation, usually indicated by a uterus at or above the level of the umbilicus. If so, initiate left uterine displacement (LUD) to relieve aortocaval compression. This can be done manually or by placing a wedge or towel under the right hip to tilt the patient 15–30 degrees to the left.

Prepare for pregnancy-specific interventions.

Once cardiac arrest is confirmed, begin BLS in pregnancy with high-quality chest compressions and ensure airway management with minimal interruptions. Defibrillation in pregnancy should be administered as in non-pregnant patients—no modifications in energy levels are needed. However, all providers should be trained in ACLS in pregnancy, which includes early consideration of resuscitative hysterotomy if there is no return of spontaneous circulation within 4–5 minutes.

Positioning and Left Uterine Displacement (LUD)

Proper positioning during CPR for a pregnant woman is critical to prevent aortocaval compression, which can significantly reduce blood flow to vital organs and compromise resuscitation efforts. Understanding and applying left uterine displacement (LUD) can improve chest compressions and increase the chance of survival for both mother and baby.

Why is full side-lying contraindicated?

A common misconception is to place the pregnant woman in a full side-lying position to relieve aortocaval compression. However, this is not recommended during cardiac arrest. Full lateral positioning makes high-quality chest compressions nearly impossible due to instability and poor access to the chest. According to the BLS pregnancy and ACLS in pregnancy guidelines, chest compressions must be performed with the patient in a supine position while applying LUD.

How to perform left uterine displacement?

LUD can be done manually by standing on the patient’s left side and gently pushing the uterus to the left. Alternatively, place a firm wedge (such as a blanket or rolled towel) under the woman’s right hip to create a 15–30 degree tilt. The pressure on inferior vena cava and aorta get relieved, improving venous return and cardiac output.

Maintaining LUD throughout resuscitation is vital, especially when preparing for perimortem cesarean delivery. It supports circulation until either return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or resuscitative hysterotomy is performed. In cases of defibrillation in pregnancy, no changes in energy settings are needed, and shocks can be delivered safely with proper positioning.

Performing High-Quality Chest Compressions

Effective chest compressions are vital during pregnancy resuscitation to restore circulation. Due to changes in pregnancy physiology, such as an improved diaphragm, minor adjustments in technique are necessary.

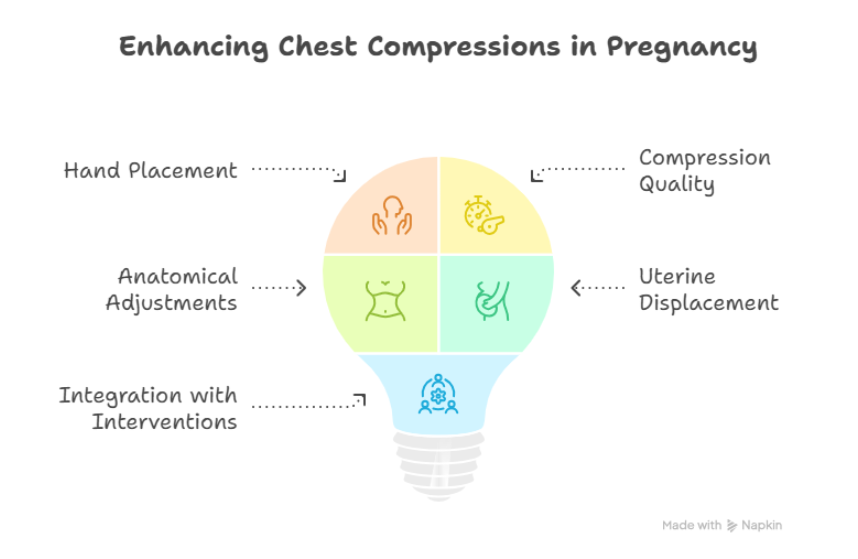

Hand placement and compression quality

Place your hands slightly higher on the sternum than usual. This accounts for the third shift of internal organs for a pregnant woman. Compressions should be delivered at 100–120 per minute with at least 2 inches (5 cm) depth.

Adjusting for pregnancy anatomy

The growing uterus affects chest anatomy and diaphragm position. Proper hand placement helps ensure compressions generate adequate forward blood flow. Combine this with left uterine displacement to relieve aortocaval compression.

Integration with other interventions

Continue compressions while other team members prepare for airway management, defibrillation, or resuscitative hysterotomy if indicated. High-quality compressions are the foundation of all advanced measures, including targeted temperature management post-arrest.

Airway management and rescue breaths

Airway control is critical during pregnancy resuscitation, as pregnancy physiology increases oxygen demand and aspiration risk. Prompt, effective airway management supports both maternal and fetal survival.

Modified techniques for pregnant women

Use the head-tilt-chin-lift method cautiously, mindful of the increased soft tissue in the airway. If trauma is suspected, use the jaw-thrust maneuver. In maternal arrest, the risk of aspiration is high due to delayed gastric emptying and reduced esophageal tone.

Ventilation guidelines

Deliver rescue breaths with a bag-valve mask using 100% oxygen, at one breath every 6 seconds (10 breaths per minute), ensuring a visible chest rise. Avoid over-ventilation, which can decrease cardiac output. Secure the airway early with advanced techniques if trained personnel are available.

Role in overall resuscitation

Ventilation must occur with minimal interruption to compressions. Ensure left uterine displacement continues during ventilation. Efficient oxygenation reduces fetal hypoxia and supports targeted temperature management if spontaneous circulation is restored.

Defibrillation in pregnancy

Defibrillation pregnancy protocols follow the same principles as in non-pregnant patients, but must be executed without delay. Cardiac arrest rhythms such as ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia require immediate defibrillation.

Pad placement and safety

Place AED pads in the standard anterior-lateral positions. If the abdomen interferes, pads may be adjusted slightly to accommodate the body’s shape. Electrical shocks do not increase the risk to the fetus. Prioritize maternal survival, as restoring maternal circulation directly supports fetal life.

No delay in defibrillation

Do not delay defibrillation for fetal monitoring, oxygen delivery, or setup of other interventions. If a shockable rhythm is identified, deliver the shock at standard energy levels. Continue high-quality compressions and left uterine displacement immediately after each shock.

Integration with advanced care

If there’s no return of spontaneous circulation within 4–5 minutes and gestational age is ≥23–24 weeks, initiate resuscitative hysterotomy per current pregnancy resuscitation guidelines. Defibrillation should never be withheld or delayed when clinically indicated.

Quick, decisive action in defibrillation pregnancy scenarios is vital. Combined with quality CPR, airway management, and appropriate interventions, timely defibrillation can be life-saving in maternal arrest causes involving shockable rhythms.

Advanced Interventions and the 4-Minute Rule

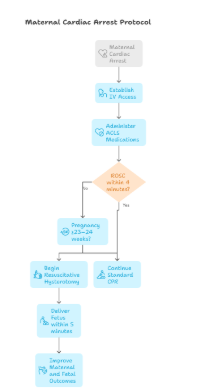

In cases of maternal cardiac arrest, rapid escalation to advanced care is essential. The pregnant CPR protocol includes specific guidelines for timing, medication, and potential delivery decisions to maximize survival for both the mother and fetus.

IV access and medication

Establish IV access above the diaphragm, typically in the upper extremities, to ensure adequate circulation during arrest. Administer ACLS medications as outlined by the American Heart Association (AHA), following standard dosing protocols. Medications should not be withheld due to pregnancy unless contraindicated.

The 4-minute rule and resuscitative hysterotomy

If there is no return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) within 4 minutes, and the pregnancy is ≥23–24 weeks of gestation, begin resuscitative hysterotomy immediately. The goal is to deliver the fetus within 5 minutes to improve both maternal and fetal outcomes. This emergency perimortem cesarean delivery relieves aortocaval compression and can significantly improve the chance of successful maternal resuscitation.

Post-resuscitation care

After achieving spontaneous circulation (ROSC) return in a pregnant patient, careful post-resuscitation management is essential to stabilize both mother and fetus.

Targeted temperature management and monitoring

Initiate targeted temperature management (TTM) if indicated to preserve neurological function. TTM can be safely administered in pregnancy under expert guidance. Continuous fetal monitoring should begin as soon as the mother is stabilized to assess fetal well-being. This includes monitoring fetal heart rate, variability, and potential signs of distress.

Transfer and ongoing care

Transfer the mother to a tertiary care center with obstetric, neonatal, and intensive care resources. Close collaboration between critical care, obstetrics, and neonatology teams ensures comprehensive care. Maintain airway management in pregnancy and monitor for complications like bleeding, arrhythmias, or multi-organ dysfunction.

Post-resuscitation care must follow the pregnant CPR protocol and include follow-up assessments for both maternal and fetal health. It is insufficient to achieve ROSC—ongoing management is vital for full recovery.

Training and maintaining lifesaving skills

Proper response to maternal arrest depends on routine, high-quality training. CPR for pregnant women scenarios are rare, but the consequences of unpreparedness are severe.

Regular simulation drills

Conduct regular interdisciplinary drills that simulate pregnant CPR protocol situations. Teams should practice initiating chest compressions in pregnancy, performing airway management in pregnancy, applying left uterine displacement, and conducting resuscitative hysterotomy. These realistic scenarios help refine timing, coordination, and role clarity in high-stress events.

Staying current with guidelines

Healthcare providers must stay current on evolving AHA guidelines and pregnancy resuscitation best practices. Updates in drug use, defibrillation safety, and post-resuscitation care are essential for effective response. Regular continuing education and certification in ACLS in pregnancy and BLS for pregnant patients ensure readiness.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Which side do you lie a pregnant woman on for CPR?

You keep the pregnant woman supine for effective chest compressions, but apply Left Uterine Displacement (LUD) by tilting her 15–30° to the left using a wedge under the right hip or manual displacement. This relieves aortocaval compression and supports blood flow during CPR.

Can you use a defibrillator for a pregnant woman?

Yes, defibrillation in pregnancy is safe. Use standard AED pad placement and shock energy. Do not delay defibrillation—maternal survival is the priority, and electrical shocks pose no significant risk to the fetus. Continue high-quality compressions and left uterine displacement throughout resuscitation.

What is a consideration when performing CPR on a patient >20 weeks?

At ≥20 weeks of gestation, the gravid uterus can compress major blood vessels, impairing circulation. Apply Left Uterine Displacement immediately. If spontaneous circulation (ROSC) does not occur within 4 minutes, initiate a perimortem cesarean delivery by 5 minutes to improve maternal and fetal survival.

Can pregnant nurses do compressions?

Yes, pregnant nurses can perform CPR, including chest compressions. However, they should monitor for fatigue and rotate every 2 minutes to avoid exhaustion. If the nurse experiences pain, dizziness, or shortness of breath, they should stop immediately to protect their health and the fetus’s.

What is the protocol for CPR in pregnancy?

Follow standard BLS protocols (30:2) with key modifications- inform EMS of pregnancy, apply Left Uterine Displacement, use 100% oxygen, consider a smaller endotracheal tube, and defibrillate without delay. If no ROSC by 4 minutes and gestation is ≥23–24 weeks, begin resuscitative hysterotomy.